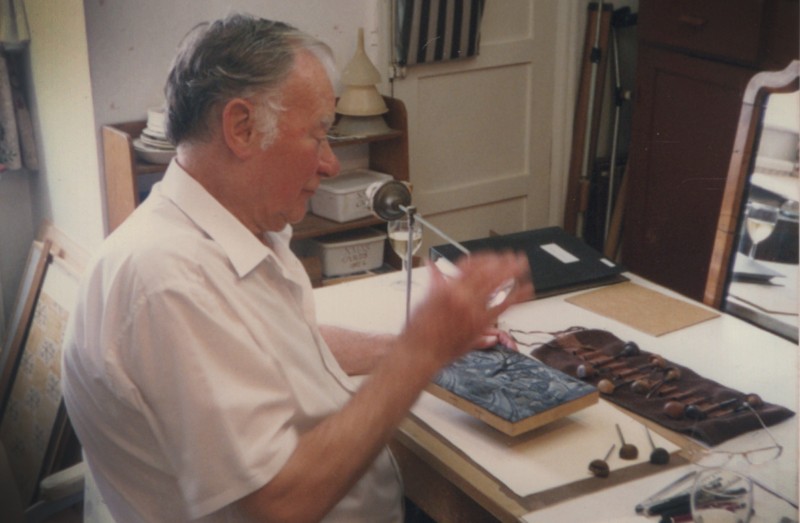

For over thirty years James Bostock combined an artistic career with that of a full-time teacher and administrator. Over that period, Bostock produced a remarkable oeuvre of paintings and prints. The process of cataloguing the seventy or so wood engravings, as well as the intaglio prints, lithographs and illustrative work has been a revelation of the breadth of subject matter and variety of style these prints demonstrate.

It was at the Royal College of Art in the 1930s, under the influence

of such tutors as Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious and Paul and John

Nash that Bostock first became attracted to printmaking, and especially

wood engraving. After distinguished war service he began to produce

wood engravings which were soon recognised for their fine craftsmanship

and artistic individuality. By 1950 he had been elected a member of

both the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers and the Society of Wood Engravers.  He exhibited regularly at the annual exhibitions of these societies

and his work was often included in the Royal Academy summer shows.

Museums and international institutions acquired his wood engravings

and Bostock quietly secured his position within the print world. There is a collection of prints by James Bostock in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London which can be viewed on this link.

He exhibited regularly at the annual exhibitions of these societies

and his work was often included in the Royal Academy summer shows.

Museums and international institutions acquired his wood engravings

and Bostock quietly secured his position within the print world. There is a collection of prints by James Bostock in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London which can be viewed on this link.

However, it was not until retirement in 1978, and a resultant flurry

of artistic activity, that James Bostock's work came before a wider

audience. Exhibitions of his paintings and prints occurred regularly

and the wood engravings were shown at the exhibitions of the newly

invigorated Society of Wood Engravers. Bostock was now able to promote not only his many

earlier works, but also the results of a productive decade. Sadly,

by 1988, deteriorating eyesight and the onset of arthritis caused

him to cease wood engraving - although, even then, he still painted

and drew with vigour.

The wood engravings continued to be shown at exhibitions and, in 1996,

Bostock was one of nineteen major artists to be included in an exhibition

arranged by Hilary Paynter (Chairman of the Society of Wood Engravers)

at the Bankside Gallery, London. This exhibition featured artists

who were members of both The Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers

and the Society of Wood Engravers. Bostock had no impressions left

of his most popular prints and Hilary Paynter kindly offered to print

some of these blocks for him. She is full of admiration for the deep

cutting and quality of the artist's blocks and described them as 'a

joy to print'.

The wood engravings continued to be shown at exhibitions and, in 1996,

Bostock was one of nineteen major artists to be included in an exhibition

arranged by Hilary Paynter (Chairman of the Society of Wood Engravers)

at the Bankside Gallery, London. This exhibition featured artists

who were members of both The Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers

and the Society of Wood Engravers. Bostock had no impressions left

of his most popular prints and Hilary Paynter kindly offered to print

some of these blocks for him. She is full of admiration for the deep

cutting and quality of the artist's blocks and described them as 'a

joy to print'.

Only a year later Bostock's work was included in Hal Bishop's landmark

exhibition at Exeter Museum, "Twentieth-Century British Wood Engraving:

A Celebration... and a Dissenting Voice". This exhibition received

an Arts Council award and is possibly the most important display of

British wood engraving to occur in recent years. James Bostock acknowledged

fulsomely the generosity and genuine interest that Hal Bishop has

shown in promoting his work Indeed a solo exhibition of Bostock's

watercolours and prints was curated by Hal Bishop at Exeter Museum

in the Following year in order to show the full range of his artistic

output.

Only a year later Bostock's work was included in Hal Bishop's landmark

exhibition at Exeter Museum, "Twentieth-Century British Wood Engraving:

A Celebration... and a Dissenting Voice". This exhibition received

an Arts Council award and is possibly the most important display of

British wood engraving to occur in recent years. James Bostock acknowledged

fulsomely the generosity and genuine interest that Hal Bishop has

shown in promoting his work Indeed a solo exhibition of Bostock's

watercolours and prints was curated by Hal Bishop at Exeter Museum

in the Following year in order to show the full range of his artistic

output.

A substantial and distinguished group of collectors has now been established

to James Bostock's wood engravings who admire not only the technical

skill of his prints but their humour, observation and stylistic variety.

- Hilary Chapman, 20th Century Gallery, Kings Road, Chelsea. November 2002.

Analysis by Simon Brett, former Chairman of the Society of Wood Engravers

The immediacy of James Bostock's wood engravings makes time collapse, yet they are also rooted in the decades in which they were produced. In viewing his works as a whole we can reconcile the vivid impact of his art, the rather different sense of time we carry within us, with the actual chronology which Hilary Chapman has so valuably researched.

Though only one print dates from the nineteen-thirties, Bostock's work first seems to speak to us with the accent of that decade, which is only natural. In common with many others, his career suffered the major interruption of the Second World War, which took six years of his life just where his education finished and his mature development should have begun. He picked up after it, therefore, with styles and attitudes formed before it.

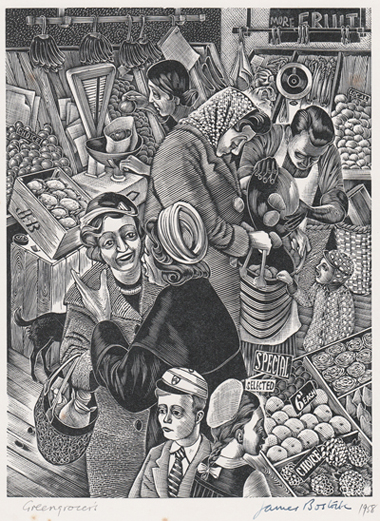

By the nineteen-fifties, however, his essays in Hayteresque modernism were completely up-to-the-minute; and the social scene depicted in 'Train Coming' and 'Greengrocers' is also perfectly true to the decade - my childhood - though it feels so much longer ago now. Our memories play us tricks. These prints remind us how much art was still in 'post-war mode' not only throughout the 'fifties but well into the 'sixties. They speak from before the watershed of that later period. After it, neither art nor the place of wood engraving within it, was quite the same, but the change did not really happen until late in the decade. James Bostock was fifty then, and well established in his manner of working; but, just at that point, he became so busy with teaching that it caused a second interruption in the production of his prints.

By the nineteen-fifties, however, his essays in Hayteresque modernism were completely up-to-the-minute; and the social scene depicted in 'Train Coming' and 'Greengrocers' is also perfectly true to the decade - my childhood - though it feels so much longer ago now. Our memories play us tricks. These prints remind us how much art was still in 'post-war mode' not only throughout the 'fifties but well into the 'sixties. They speak from before the watershed of that later period. After it, neither art nor the place of wood engraving within it, was quite the same, but the change did not really happen until late in the decade. James Bostock was fifty then, and well established in his manner of working; but, just at that point, he became so busy with teaching that it caused a second interruption in the production of his prints.

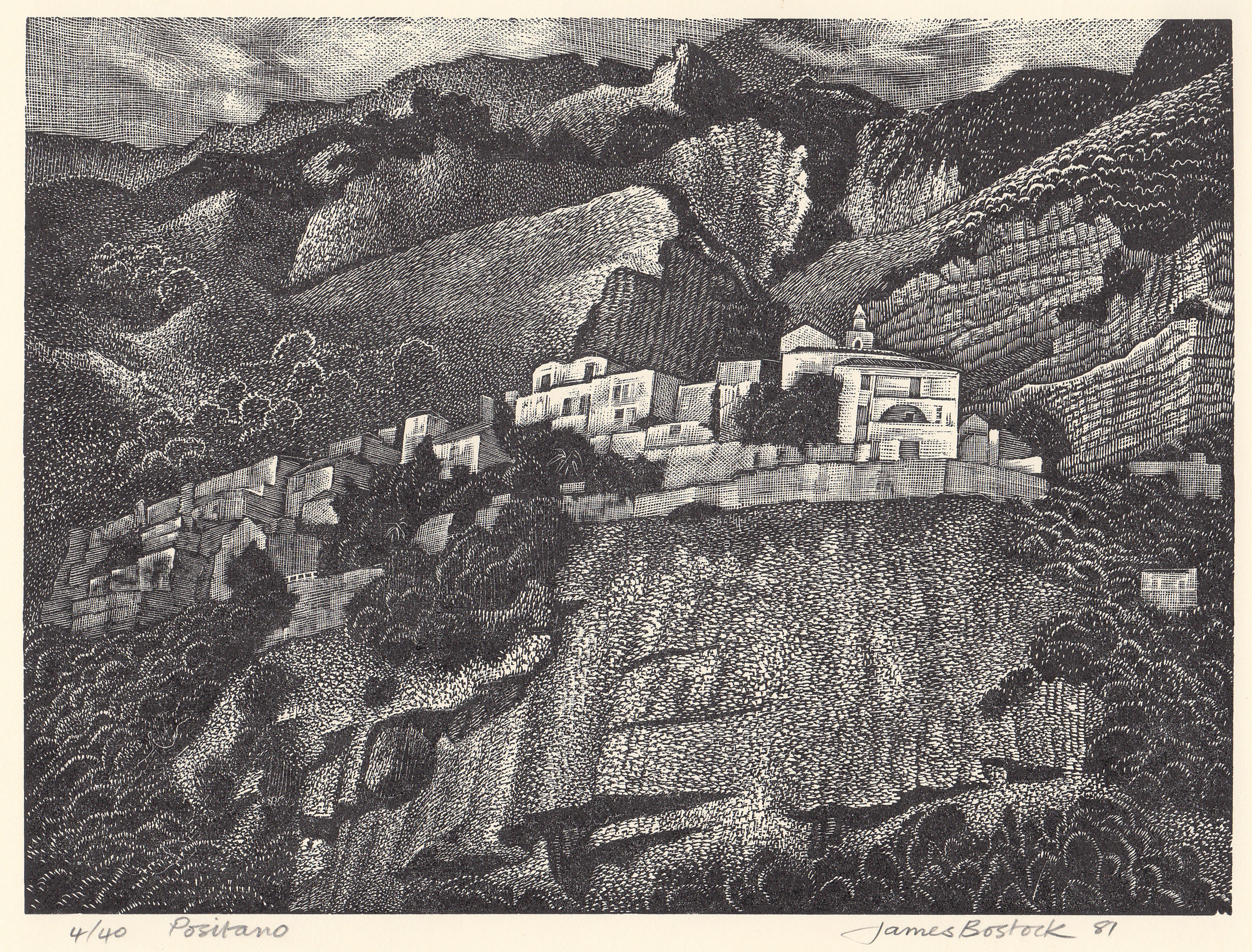

So the correspondence between Ducks in the Wood of 1946 and Black Park I of 1960 should not surprise us. Those virtuoso engravings Brentford Lock and The Mirror, with their Hayteresque swirls, demonstrate, as they must have done to the artist at the time, that there was every bit as much rhythm in his more naturalistic landscapes. When he picked up his burin afresh in the early nineteen-eighties, after retiring from teaching and administration, it is right that it was in a different mode and spirit again. What wetter waves have ever broken onto paper! Considerable tonal risks are taken in Positano and Near Ullswater, made of shifting greys rather than the bold blacks and whites of earlier years. These prints impose less on nature. They have a touching awe before it. Yet across fifty years there is an immediately recognisable consistency; the work of a long life united by a vivid and ebullient enthusiasm for the things seen.